You wouldn't execute a file

In order to make puzdug-x86, I had to learn a bit of bare metal x86 assembly. I learned something handy early on. Even though I was trying to make my program directly bootable, I could make some tiny tweaks to the code and build it as a DOS-compatible COM executable instead.

This was convenient for my compile-run loop - instead of waiting a few seconds to reboot a VM and having it steal my mouse cursor, I could leave DOSBox on and rerun PUZDUG.COM every time I made a build.

I could also put off worrying about program size until later - direct boot on BIOS gets slightly more complicated if your program exceeds 510 bytes, but on DOS you can load COM files up to the maximum size of 65,280 bytes without having to think about it.

What’s different between a COM file and a BIOS-bootable MBR? Very little. As a file format, COM (short for “command”) is solid executable binary; there is no header, metadata or wrapper as you would find with ELF, PE or Mach-O on modern systems, so it is largely identical to the disk image you would copy into the MBR for BIOS boot.

With regard to the code and build process, there are some differences between the formats, but I want to focus on one in particular - at the start of your program, you need to adjust a magic value. Depending on the platform, you need to choose one of the following:

org 0x0100 ; For DOS

;--------;

org 0x7C00 ; For BIOS boot

org is not a CPU instruction, it is an assembler directive - it tells the assembler to assume that when the program executes, it will be loaded into a particular offset in memory (relative to the current memory segment, wherever that may be).

This matters because memory addresses are pre-calculated and baked into certain instructions - the assembler keeps track of where things are in relation to each other as it assembles the binary so that it bakes in the right values.

For instance, when writing assembly, jmp feels like “jump to this line of the file”, but in the final binary representation, it means “jump to this point in memory”.

Does that seem like a trivial distinction? Let me put it this way: the program on disk is but a pale image (pun intended); the true, living process exists only in memory. Something else (like the OS or the BIOS firmware) puts it there and hands over execution to it. Hopefully the program is in the right spot and all the segment registers are set correctly, or else all those baked-in addresses will be pointing to the wrong place! Most programs do not load themselves, so in some sense they are at the mercy of others to be loaded in the right place so that they function correctly.

Sidebar: x86 multitasking challenges

Considering that COM programs in DOS get direct access to physical memory (no virtual memory! not even memory protection!), it's no surprise that only one program can execute at a time. Evolutions of the format for executables made programs more flexible with respect to how they were loaded, which in turn helped operating systems take advantage of evolving memory protection and multitasking features on CPUs.

As memory grew there were also terminate-and-stay-resident (TSR) programs that could enter a dormant state in memory and pass control back to the shell, allowing users to switch back and forth between several different programs without losing their place. More on DOS-era executable formats and memory in DOS Memory Models by Julio Merino.

In the era preceding DOS, there was so little memory to begin with that just loading a program might eat up a significant fraction of RAM. The more functionality you added to your program, the (appreciably) smaller amount of data it could effectively operate on - what a terrible tradeoff! Thus it could make sense to split a program into smaller pieces and run them separately. This is like the opposite of multitasking!

Programs that were split up like this could use a technique similar to TSR called an overlay to stretch the available memory - see below quote from Kevin Boone on DOS predecessor CP/M.

In a machine with 64kB RAM, the program had about 56kB to use. That 56kB would include the program's executable code, plus any data it was working on. In practice, many programs made use of "overlays" -- the program would have a core element that remained resident in memory all the time, and interchangeable sections that were loaded from disk as required. This loading was slow going with an 8" floppy drive, but it allowed for programs with a high level of functionality.

Let’s look at a little hello world program and assemble the same code with different org values and see what changes in the binary.

I assembled it with nasm -f bin hello.asm twice - once with org 0x0100 at the top, and once with org 0x0200.

Below is the original assembly listing and two disassemblies of the assembled binaries with different org values.

For the lines with memory addresses in the disassembly, I show the source and the two disassemblies inline.

start:

mov bx,string ; Copy the pointer (source)

;--------;

mov bx,0x0117 ; Copy the pointer (org 0x0100)

;--------;

mov bx,0x0217 ; Copy the pointer (org 0x0200)

print_loop:

mov al,[bx] ; Get the char value

test al,al ; Test for 0 value

je end ; Break out of loop (source)

;--------;

je 0x0C ;(+12) ; Break out of loop (org 0x0100)

;--------;

je 0x0C ;(+12) ; Break out of loop (org 0x0200)

push bx

mov ah,0x0e

mov bx,0x000f

int 0x10 ; Call print

pop bx

inc bx ; Point to next char

jmp print_loop ; Loop (source)

;--------;

jmp 0xEE ;(-18); Loop (org 0x0100)

;--------;

jmp 0xEE ;(-18); Loop (org 0x0200)

end:

int 0x20 ; exit to DOS

string:

db "Hello, world",0

In this program, there is just one instruction that depends on org - mov!

As you can see, adding 0x0100 to org results in adding 0x0100 to the pointer stored in bx.

On the other hand, the jumps (je/jmp) are relative to the current instruction.

This was a surprise to me - I was expecting more instructions to be sensitive to org.

In fairness, x86 has a lot of different types of jumps, including ones with absolute addressing schemes, but most of them are relative like the ones seen here.

But in any case, even this one instruction is enough that the program breaks when org is changed.

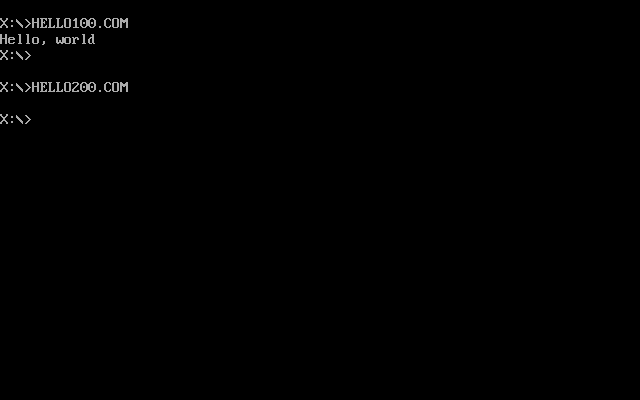

Trying to run the two assembled versions in DOSBox, the org 0x0100 build runs properly, and the org 0x0200 build just exits!

In modern 64-bit x86 assembly, it’s possible to completely avoid absolute memory addressing and write a position-independent program that functions properly regardles of where it’s loaded. It may be possible to emulate that in the ancient 16-bit x86 that was around in the days of DOS - I leave that as an exercise for the reader ;)

Getting back to puzdug-x86, the code eventually blew past the 510 byte limit for BIOS boot as I kept adding features and logic without making any effort to optimize for space.

When booting into it, the BIOS would load the first 510 bytes into memory for me and start executing it, but the remaining code was left on the disk, which is to say at some point the program would run off the rails unless I loaded the rest into memory myself.

Photographer: Peter MacCallum January 20, 2001 Series 572, File 77.

Photographer: Peter MacCallum January 20, 2001 Series 572, File 77.

This is not that hard to deal with - I put some code in the first 510 bytes that would grab the remainder of the program and load it in memory.

Nevertheless, there’s a delicate contract - the loader loads the remaining code from the right point on disk, into the right part in memory, and jmps to the right memory address to hand off execution to it (in this case using an absolute address).

~

By modern standards, MS-DOS and its contemporaries are barely OSes. But they do give us a feature that we take for granted, an implicit promise that has been kept - you can navigate to a folder on disk and just run an executable, almost as if the program was running right off the disk itself. Neither the programmer nor the user need to worry about moving the program from disk to memory. Just press enter. ↩️